Miss B* raised a fascinating question:

In Alice Lucy Trent’s The Feminine Universe, a key Aristasian study text, the first chapter, entitled “The Image of the Cosmos”, begins with a quotation from Friedrich Nietzsche: “The total nature of the world is…..to all eternity chaos, not in the sense that necessity is lacking, but in that order, structure, form, beauty, wisdom and whatever other human aesthetic notions we may have are lacking…..Let us beware of attributing to it heartlessness and unreason or their opposites: it is neither perfect nor beautiful nor noble, and has no desire to become any of these…..neither does it know any laws. Let us beware of saying there are laws in nature. There are only necessities. There is no one to command, no one to obey, no one to transgress….. Let us beware of saying that death is the opposite of life. The living being is only a species of the dead, and a very rare species.”

A “species of the dead”, eh? I know I am not very good in the mornings, but I object to being called a “species of the dead”! What the blazes is old Fred driving at with that particular line of thought? (Oh dear, I fear that I am sounding rather like my sister, Eve! She came home for a weekend visit, and perhaps some of her “banter” has been left lurking) What I mean to say is, how can it be that “the living being is a species of the dead”? and why “a very rare species”? Also, what does Miss Trent intend in opening her book with such a quotation? The subtitle to The Feminine Universe is “An Exposition of the Ancient Wisdom from the Primordial Feminine Perspective”. So how does Herr Nietzsche lead in to such themes? I suppose one clear answer is to get through the entire chapter and see the full picture.

Miss Serendra Serelique replied:

To begin with, those unfamiliar with the chapter being discussed may find it here. As you will see, the quotation with which it opens is put forward not as an example of the Aristasian philosophy, but of its opposite. The point being made is that while this outlook may seem stark and brutal, it is logically the same as the popular “scientistic” (as opposed to scientific) view of the universe that is inculcated by the schools and mass-media of Telluria and believed by most people.

What we have to consider here is the particular expression used by Nietzsche: “Let us beware of saying that death is the opposite of life. The living being is only a species of the dead, and a very rare species.”

This is the culmination of a series of statements denying that the universe possesses order, harmony or intelligence — a denial that is perfectly logical, and indeed necessary, if one adheres to the view that the universe is simply an accidental phenomenon — a chance falling-together of atoms and molecules — rather than a manifestation of a higher or spiritual principle. And let us note that these two views are the only two possible. There is no middle ground between them. Nietzsche’s view may sound extreme, but it is not extreme. It is only a statement in very plain and frank language of what the materialist or accidentalist view of the universe really involves.

And let us further note that this materialist or accidentalist view, while it is utterly predominant in the thought-world of modern Telluria, is a very isolated and strange one. It has never been conceived of in any continent but Europe, and not in Europe before the seventeenth century. Every other people, every other civilisation, has adhered to some form of Essentialism. That is, to the belief that the manifest universe is the creation or reflection or emanation of a spiritual Principle, whether that Principle be called God or the Tao, Brahman or Atman.

And even though such a view has its roots in the seventeenth-century “enlightenment” (a curious name if ever there was one!) it did not become fully formed or even fully possible until Nietzsche’s time — that is, the later nineteenth century. So Nietzsche is considering a new phenomenon; a new view of the world: a view so appalling that Nietzsche expresses his reaction to it thus:

Who gave us a sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What did we do when we unchained this earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving now? Away from all suns… Are we not straying as through an infinite nothing? Do we not feel the breath of empty space? Has it not become colder? Is more and more night not coming on all the time?

He is not opposed to this view. He is promoting it. But he is expressing it in all the starkness of its real implications. Miss Trent notes later in the book that while Nietzsche is expounding a radically anti-traditional view he is doing so in terms of traditional symbolism. Everywhere the Sun symbolises the Spirit or the Divine. Again and again in tradition we find the Great Chain which connects all beings and runs from Heaven (the Sun, the Spirit) to earth. Nietzsche talks of the modern accidentalist philosophy in terms of breaking the Chain and losing the light and warmth of the Sun.

So on to this enigmatic statement: The living being is only a species of the dead, and a very rare species. On the face of it, that is not so terribly mysterious. If life itself (according to a certain rather tendentious extension of Darwinian theory, which made total accidentalism theoretically possible for the first time) is the mere falling-together of carbon and hydrogen molecules under certain freak circumstances — if life, in other words, derives purely and solely from dead matter, then we may say that the living being is a species of the dead. A very rare one because only by the most extraordinary set of coinciding chances can this “life” be produced at all.

This, clearly enough, is what Nietzsche means; but what a peculiar and very telling way of expressing it. As in the Sun and Chain passage above, the entire background to this anti-traditional exposition is Tradition itself. The living being is a species of the dead: why? Because Life in the sense that Tradition has always understood it — the Divine Spark, the Breath of Spirit — is absent.

By a curious and very profound use of Language, Nietzsche reveals that in his heart he knows that the accidentalist view of life, the falling-together of bits and pieces of dead matter, is not actually life at all. Such a life, if it were (as he believes is to be) the nature of living beings, would not really be life at all, but only a species of the dead.

Comments Off on Quoting Nietzsche

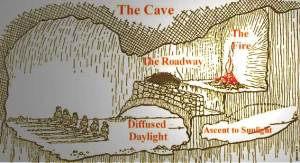

Now that cave is the material world, and the shadows are the material things we see about us. Every tradition teaches that the material things we see are the shadows or reflections of higher things. Everything on earth has an Archetype, which is its true and perfect Form, of which the material entity is only an imperfect shadow.

Now that cave is the material world, and the shadows are the material things we see about us. Every tradition teaches that the material things we see are the shadows or reflections of higher things. Everything on earth has an Archetype, which is its true and perfect Form, of which the material entity is only an imperfect shadow.

As this year started on a Friday, it is ruled by Sai Sushuri. This is an edited version of the article on the janya from

As this year started on a Friday, it is ruled by Sai Sushuri. This is an edited version of the article on the janya from